When I was at Art School in the 90s

Lloyd and Jamie, London, 1998.

Text Jamie Atherton

I recently read Neil Bartlett’s Ready to Catch Him Should He Fall for the first time. Published in 1990, it describes a gay London topography of the preceding years. Bartlett’s is a city I recognise. When I arrived in 1995 it felt similarly empty, especially in the east where the towpaths I’d follow for hours were overgrown with brambles and vast wastelands lay dormant, unaware of their Olympian future (starchitect pleasure domes, parachuting monarchs).

As in Bartlett’s novel, this was a dangerous landscape for an eyelinered young homo to be flitting about. My wanderings were tinged with fear: lone strangers, groups of lads, flashes of panic upon realising I was truly lost. East London wasn’t empty, of course; lives were being lived everywhere. But when I was at art school in the 90s, I was new to the metropolis and seeking something else. In a wooded cemetery I scribbled over the sharpie swastikas on a bench with glitter-pen.

Jamie and Lloyd, London, 1998.

It’s an emotive title Marc has retroactively given this body of work. “Art school” is such a good phrase — as if it was the 60s and we were at the Slade, accused of being part of a gay mafia by seriously bearded straight boys in roll-necks. All credit to Marc for imbuing the project with a dose of nostalgia — a sensation more about the longing than what was actually real.

These photographs have me thinking a lot about realness. The four of us living in that house in Stratford did everything to avoid it — constantly dying our hair, pretending the matted stray cat was ours, planting a garden of plastic flowers in the living room. I wore fake glasses for a while; a handsome tutor at the art school asked if they were real. No, I confessed. Wrong answer, he admonished with a wry smile. This has stuck with me. I felt embarrassed at the time, like I wasn’t committed enough to the pretense. But in retrospect, I rather like that I owned up to the artifice — declaring my queerness; a constant game of dressing up and trying on. For weeks those glasses framed my gay gaze, much as the camera’s viewfinder framed that of our new friend, Marc Vallée.

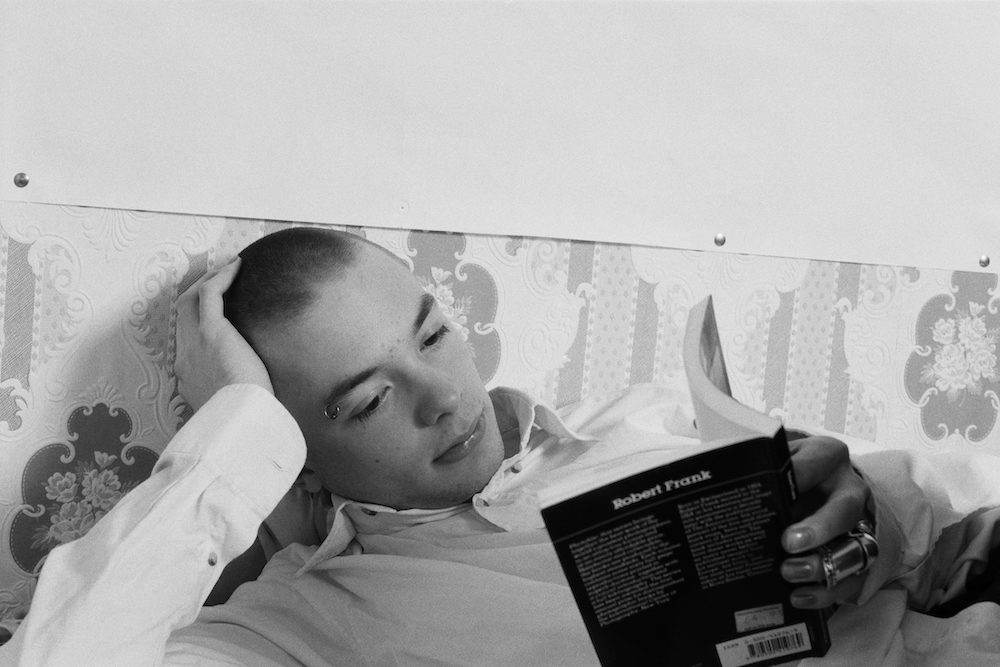

Jamie, London, 1998.

Marc was an MA student, a little older and more worldly than us. He carried a skateboard and had met Derek Jarman. He was a flirt, unabashed about his sexuality, which of course informed his horny, boy-crazy work. But that was by no means the entirety of what his camera saw. Revisiting these pictures I realise they’re not just about the erotics of half-naked pasty twinks lounging around (although they certainly are about that), but moreover seem to invite us into an almost spectral realm between the real and unreal, a sort of photographic witching hour.

The dilapidated house, constantly at risk of disappearing into its own terrifying basement, was real. The remarkable wallcoverings chosen by our landlord (aka The Reverend) were certainly real (almost surreal), as was our extensive collection of junk, all shown just as it was: Hulk Hogan tank top, Sesame Street toys, a Carl Andre-like arrangement of Silk Cut boxes, Fire Walk With Me poster, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” poster, a Club Kitten flyer, a multitude of televisions, spray-painted bedding, a Robert Frank book, white DMs, that painting from Abigail’s Party, a panoply of pound shop plastic.

Lloyd, London, 1998.

What wasn’t real was the suggested relationship. Lloyd and I, although close friends, were never lovers. He was bi, but in a very nineties way, and besides, I was wholly devoted to the boy in San Francisco I’d later marry (look closely, he’s very present here — I find my own private punctum in the pictures of him dotted around my room). Nonetheless, through the performativity of collective art-faggotry, an ambiguous reality presented itself.

Revisiting these fin-de-siècle photographs twenty-two years later marks one of a couple of recent encounters with my younger self as told by other authors. In this instance, I recognise a passing flicker of time lived and seize on the autobiographical, aware though I am that there are many other stories here, not least that which occupies the territory radiating outward from the flagpole-like “I” in Marc’s title.

I find myself looking for ghosts, not so much from the past, but rather of the future. In the coming months the bohemian love-in would sour (perhaps that wallpaper did a Charlotte Perkins Gilman on us). Everyone else moved out before the lease was up, and I was left in the dark, rummaging behind damp couch cushions in search of coins for the electric meter.

I moved to San Francisco to be with the real boyfriend. Some time later, we drove to Las Vegas for the wedding of Lloyd and another of the housemates. They divorced not long after. She remains one of my dearest friends, and Lloyd... well, who knows? No one’s heard from him in years.

Lloyd, London, 1998.

Lloyd and Jamie, London, 1998.

Lloyd, London, 1998.

Jamie, London, 1998.

Lloyd and Jamie, London, 1998.

Lloyd, London, 1998.

Lloyd and Jamie, London, 1998.

Jamie, London, 1998.

Lloyd, London, 1998.

Jamie Atherton is an artist working with performance, writing, drawing and video. He is the founder and editor of Failed States, a journal that collates and investigates ideas around place. Jamie is interested in the publishing process’ potential for research, collaboration, assembly and dissemination.